Coal mines in Jharkhand help retrace a long-lost world

Coal mines in Jharkhand help retrace a long-lost world

Open cast coal mines in Jharkhand have provided evidence of a lost ecosystem that existed much before humans or even dinosaurs existed. Evidence buried in the mines helped retrace the dense swampy forests and network of rivers that prevailed in India which formed part of the southern supercontinent Gondwanaland, nearly 300 million years ago.

The study reconstructs the Gondwanan environment occasionally kissed by the sea and could provide insights into how sea level rise due to climate change can reshape continental environments

Earlier studies proposed numerous theories which attempted to explain pathways of sea incursion on the basis of evidences found in fauna and sediments collected from different outcrops and coalfields across India. However, the area of study remains much debated as the occurrences of prehistoric marine floods or Permian Sea transgression are sporadic and documented only in a limited number of localities.

A new multidisciplinary study led by Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences (BSIP), an autonomous institute of the Department of Science and Technology (DST), collected palaeobotanical and geochemical evidence from the Ashoka Coal Mine in Jharkhand’s North Karanpura Basin. It uncovered an extraordinary fossil record of ancient plants and microscopic chemical signals that together paint a vivid picture of this vanished ecosystem from the time when India alongside Antarctica, South Africa, South America, and Australia constituted Gondwanaland.

Fig.1: Plant fossils ( ̴ 290 m.y.) recorded from the Ashoka Coal Mine section a) Glossopteris searsolensis, BSIP- 48382, b) G. giridihensis, BSIP- 48383, c) G. subtilis, BSIP- 48384, d) G. stenoneura, BSIP- 48385, e) Unidentified ovuliferous fructification, BSIP- 48390, f) Reconstruction of the unidentified fructification, g) Glossopteris nautiyalii, BSIP- 48394, h) G. zeilleri BSIP- 48395.

The reconstruction of Gondwana Environment and associated palaeo vegetation revealed abundance of Glossopteris, an extinct group of seed plants that once dominated the southern continents.

Fossils of at least 14 different species of Glossopteris and its close relatives, were found preserved in shale layers in the coal mine as delicate leaf impressions, roots, spores, and pollen grains.

A globally significant discovery was the first-ever juvenile male cone of Glossopteris in Damodar Basin. It is a botanical ‘missing piece’ that can help scientists understand how these ancient trees reproduced.

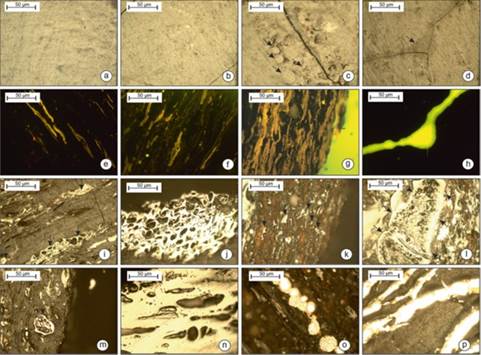

Fig. 2:Photomicrographs of different petrographic constituents of coal samples-a-b) collotelinite; c) corpogelinite (arrow); d) oil smear (arrow); e-f-g) sporinite; h) exsudatinite (fluorescence view of d); i) semifusinite (arrow); j) fusinite; k) inertodetrinite (arrow; normal view of g); l-m) funginite; n-p) pyrite-massive, framboidal and cell filling form, respectively. Photomicrographs a-d and i-p were taken under incident white light; photomicrographs g-h was taken under blue light excitation (fluorescence) mode.

Examination of the coal and shale pellets under the microscope, indicate presence of framboidal pyrite– tiny raspberry-shaped mineral clusters, and unusually high sulphur levels in the coal and shale. This suggested brackish-water conditions, unusual in coal deposits within the basin, thereby providing evidence of marine incursion and its pathway.

Chemical analyses of organic molecules (using Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry) suggested a possible marine incursion around 280-290 million years into the Damodar Basin and illustrating the pathway of Permian Sea as it advanced from Northeast India into Central India.

The findings published in the journal International Journal of Coal Geology brought valuable insights into the sedimentation history of the coal bearing succession along with marine signature at Ashoka Coal Mine in North Karanpura Coalfield.

Drawing parallels between past marine incursions and current sea-level rise associated with polar ice melt, the study could throw light on the implications of potential future encroachment of marine environments onto continental landscapes under ongoing global warming.

Publication link: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2025.104860